A collection of printed sheet music with dedications and a school reader is kept in Vače Primary School.

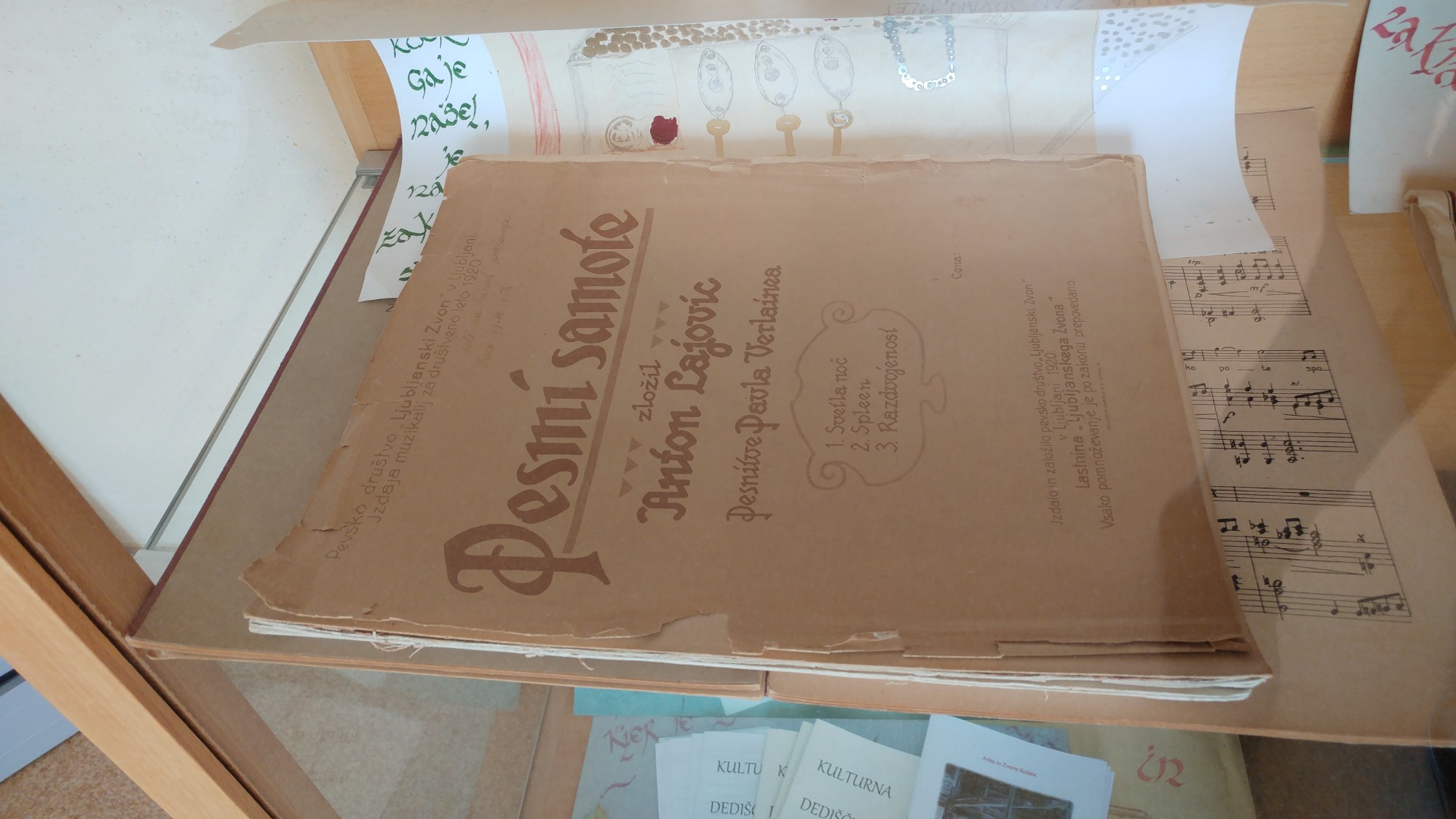

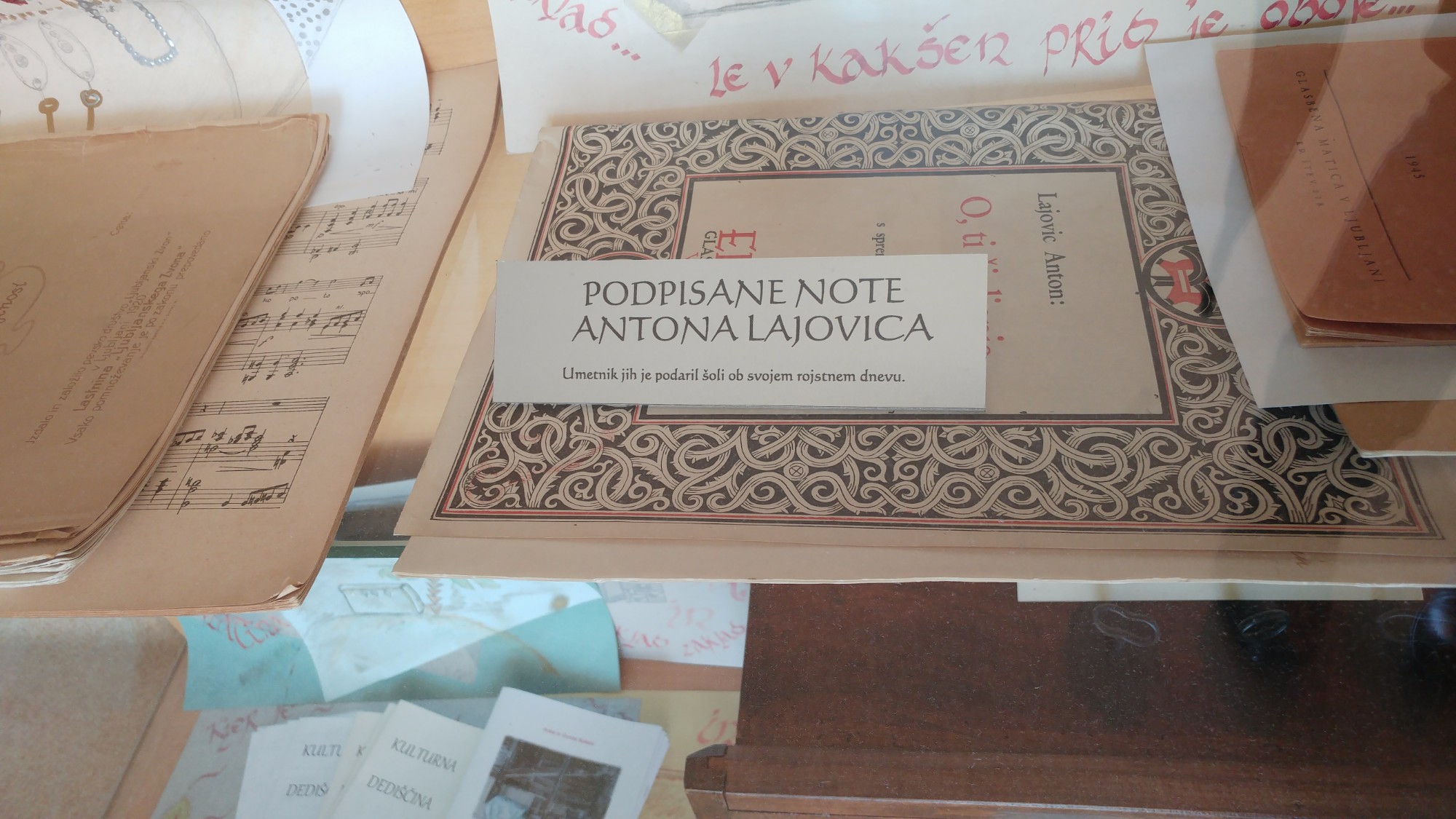

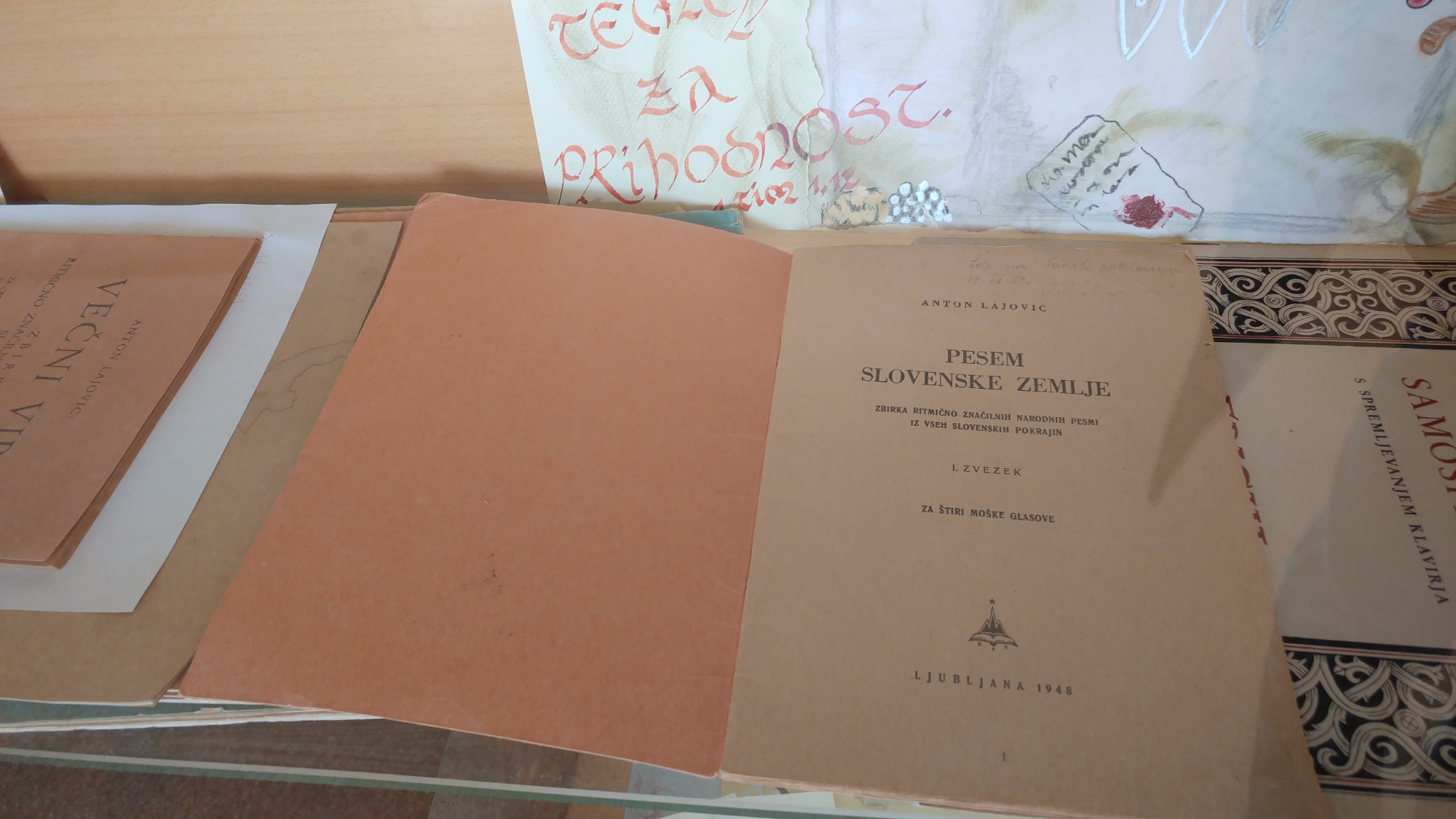

On the occasion of the inauguration of the Vače Primary School in Anton Lajovic’s hometown, the composer donated some original scores to the school. The scores include signed originals of Anton Lajovic’s sheet music, which are kept in the school.

List of scores:

- Pesmi samote (Songs of Solitude, 1920) – the volume is in an advanced state of disintegration

- Devet samospevov (Nine Lieder, 1931)

- Gozdna samota (Forest Solitude, 1932)

- Iz nove muzike (From New Music, 1932)

- Dva samospeva (Two Lieder, 1932)

- Večerna (Evensong, 1934)

- O, ti življenje (O, This Life, 1934)

- Otvi (Wild Ducks, 1942)

- Žalostna deklica (Sad Girl, 1942)

- V mraku (At Dusk, 1942)

- Psalm 41–42 (1943)

- Večni vir (Eternal Source, 1945)

- Iz mladih dni (From Days of Youth, 1948)

- Tri pesmi (Three Songs, 1952)

Anton Lajovic

Through the duality of his cosmopolitan breadth of vision and narrower national focus, composer, publicist, critic and academician Anton Lajovic (1878–1960) exerted a unique influence on Slovenian music culture. Namely, in his creative pursuits, Lajovic followed in the tradition of German late-romantic music, while through his engagement in institutions, predominantly as the key figure of the Glasbena matica Music Society, he steered the course of Slovenian music into narrower, nationally-oriented tendencies.

Lajovic received his first music lessons at the Glasbena matica Music School in Ljubljana from mentors Matej Hubad and Anton Foerster, and subsequently continued his education at the Vienna music conservatory, where in 1902 he completed his composition studies in the class of Robert Fuchs. Apart from music, Lajovic also graduated in law from Vienna University, and served as a judge, first in Brdo, then in Kranj, and subsequently in Ljubljana and Zagreb. He successfully navigated his two careers, the musical and legal. He taught at the Glasbena matica Music School, served as member of the Matica Music Society’s Board and as répétiteur at the Ljubljana Opera. He crucially influenced the development of Slovenia’s publishing and education sectors and boosted its concert life. After WWI, Lajovic reinvented the former German Philharmonic Society as a Slovenian entity and established it as a subsidiary of the Glasbena matica Music Society.

Lajovic expounded his aesthetic musical values, firmly lodged in patriotic consciousness, in his periodicals (Cerkveni glasbenik, Novi akordi and Glasbena zora – Church Musician, New Chords, Musical Dawn). He fiercely opposed modelling either Slovenian concert programme policies or new music output on the German musical tradition. Paradoxically, though, he did not adopt these policies, to which composer Marij Kogoj and musicologist Stanko Vurnik raised strong public objections, in composing his own music.

Lajovic incorporated elements of German late-romantic music, as well as aspects of impressionism and Slovenian folk music into his musical idiom. Although finding his main vehicle of expression in vocal music and touching on the instrumental genre only briefly in his oeuvre, he nevertheless scored some valuable instrumental works, e.g. orchestral compositions with the common title Pesmi mladosti (Songs of Youth – Adagio, Andante, Capriccio) and the symphonic poem Pesem jeseni (Song of Autumn).

Lajovic’s lieder are his crowning achievement, most notably Mesec v izbi, Bujni vetri v polju, Pesem o tkalcu and Begunka pri zibeli (Moon in the Chamber, Strong Winds in the Field, Song about a Weaver, Fugitive by a Cradle), which are distinguished by the lush chromaticism characteristic of late romanticism. While Lajovic’s choral collection Dvanajst pesmi za moški, mešani in ženski zbor (Twelve Songs for Male, Mixed and Female Choirs) reflects influences of Slovenian folk songs, his vocal compositions display impulses of romantic lyricism and hints at thematic composition, as well as traces of influences from Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss and Franz Schreker.

The gap in Lajovic’s doctrine between the views he professed and those he actually practised has to be understood in the light of the specific historical and political context of the interwar era, a period profoundly marked by the incorporation of Slovenian provinces into the common Kingdom of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians. After WWI, the ‘healthy’ competitiveness between ‘Slovenian’ and ‘German’ composers and musicians, a rivalry characteristic of nineteenth-century music circles within the Habsburg Empire, was succeeded by more vigorous national discords. Thenceforth, nationally conscious tendencies echoed in the music of numerous composers, either through a renunciation of German models or a search for musical foundations totally independent of western European trends. Anton Lajovic fervently espoused these principles in his publications.

Although in his compositions, Lajovic did not venture beyond the confines of a late-romantic idiom, his engagement with current musical issues and his creative endeavours laid the foundations for Slovenian musical life in the first decades of the 20th century and indicated the course of further development.

Maia Juvanc