Navje Memorial Park provides the final resting place for numerous illustrious Slovenians, including several distinguished figures in Slovenian music history. In 1936, the dilapidated municipal graveyard was redesigned as a memorial park according to plans by Jože Plečnik, Ivo Spinčič and Anton Lap. The site has Ljubljana cultural heritage status and has enjoyed, since 2001, protection as a cultural monument of local significance.

The old Ljubljana graveyard was closed for burials in 1906, and a new location was set aside for the purpose, the Cemetery of St Cross, or the present-day Žale. In 1932, the restoration of the neglected old cemetery was entrusted to architect Jože Plečnik, who had two ideas. While in line with the first, children would still be buried in the old graveyard, the second envisaged a monumental sanctuary, a shrine of glory – a Pantheon of notable Slovenians.

When in 1936 the Ljubljana Diocese donated an additional piece of land to the Municipal Council, it was decided to repurpose the area as a memorial park containing headstones of esteemed Slovenians – “Navje” (TN: the place of the dead, according to Slovenian folk mythology). The name attached to the memorial park was suggested by Josip Wester. Between 1936 and 1938, several graves and headstones of notables were moved to Navje.

Landscaped with trees and shrubs, the park contains various headstones and the four Plečnik columns which used to stand in front of the Glasbena matica Music Society. The main architectural focus is on the classicistic sepulchral arcade housing the headstones.

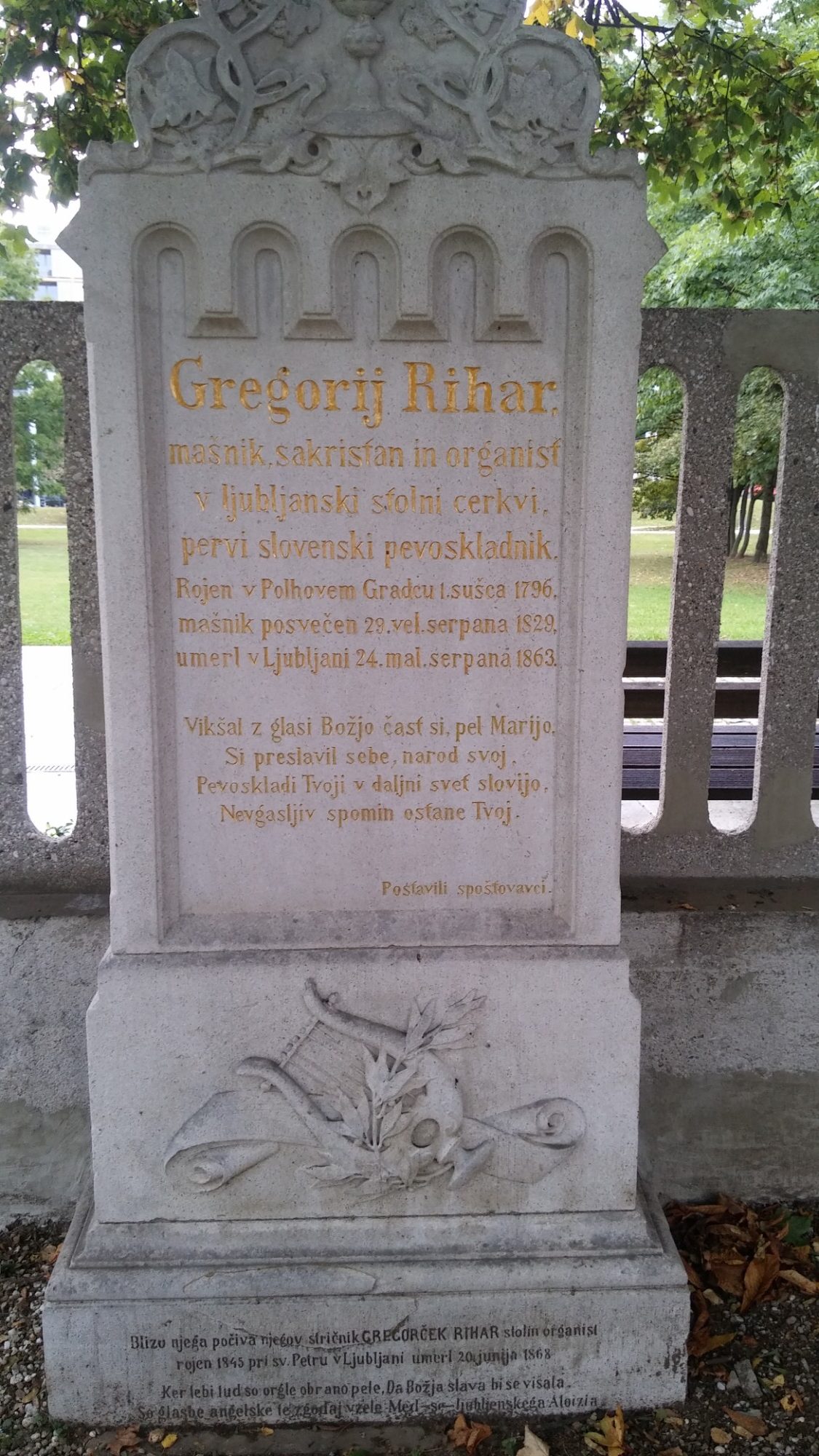

Among the gravestones of numerous artists, scientists, politicians, priests and other influential figures who steered the course of Slovenian history between the early 19th century and the beginning of the 1940s, Navje also includes memorial stones of composers, conductors and music teachers, such as Jurij Flajšman, Gašpar Mašek, Anton Nědved, Vojteh Valenta and Gregor Rihar.

Maia Juvanc

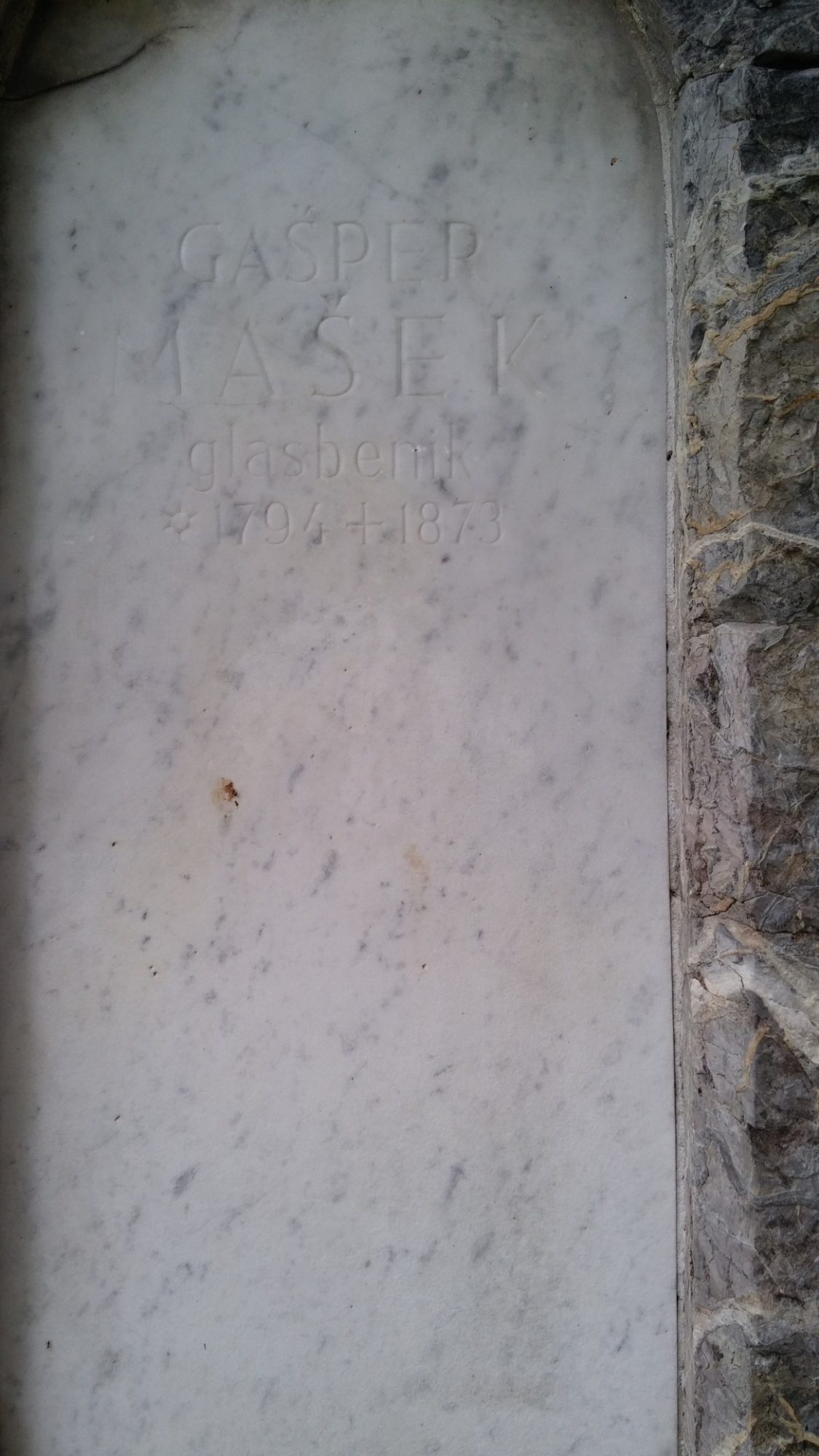

Gašpar Mašek

A naturalised Slovenian of Bohemian descent, the versatile musician and composer Gašpar Mašek (1794–1873) left a deep mark on the Slovenian national memory during the nascence of bourgeois culture. In his compositions, he mainly employed the classicistic idiom.

In the 19th century, several well-educated musicians and composers of Bohemian or German ancestry came from Bohemia, leaving their homeland and establishing themselves in Slovenia, where they played an important part in laying the foundations of middle-class culture and music.

Mašek embarked on his musical career in the Russian Empire, but the escalating Napoleonic Wars frustrated his ambitions. Returning to Prague, he followed in the footsteps of his father Vincenc, a piano virtuoso, and became an organist and choirmaster at the Church of St Nicholas. Writing mainly religious choral music during his early composing period without having any particular affinity for it, Mašek left for Graz, where he served as a conductor of the local Estates Theatre. Soon thereafter he accepted the invitation of the Philharmonic Society to move to Ljubljana and occupy the position of Society Director. During his tenure, he expanded the ranks of the orchestra and established a male choir. At the time, Mašek was one of the few educated musicians in Ljubljana, and consequently much in demand. Apart from being the theatre Kapellmeister, he was principal of the Philharmonic Society’s Music School, where he also held a teaching post. By force of circumstance, he also had to teach at the music school of Ljubljana elementary school.

Although at the time waves of nationalistic fervour had yet to sweep over Ljubljana, it was already before the March Revolution in the Habsburg areas that Mašek felt a deep kinship with Slovenian intellectuals and developed a close relationship with them. The death of Matija Čop caused him great anguish, reflected in his lied Dem Andenken k. k. Lizeal-Bibliothekars in Laibach, Mathias Zhop, a setting of a poem by Franz v. Hermannsthal. Although traces of romanticism are seen in his compositions of that period, Mašek later repeatedly returned to classicism, which was more firmly embedded in his musical idiom.

With his theatre music, the operas Emina and Die Unbekannten, and the operetta Die Strafbaren, he filled the void in the current repertoire of this genre and, moreover, fostered the development of chamber music in Ljubljana. His Klavirski kvartet (Piano Quartet) is one of the first chamber works in the history of Slovenian music. By mid-century, he had also scored four waltzes for piano, several lieder and lighter marches, quadrilles and variations on diverse themes.

A highly sought-after musician, his engagements prevented him from more fully devoting himself to composing. He could do so only after the March Revolution. Between 1848 and his death Mašek composed music that echoes nationalist feeling yet lacks the fervency that would rank him among patriotic composers. He undeniably felt an affinity for Slovenian culture, a sentiment evinced in his musical creativity, which promoted the cause of the national movement.

Mašek could not speak Slovenian, which was not uncommon at the time. Although of Slovenian extraction, several of the leading personalities of the Slovenian national movement were unable to use the language fluently. Although German was still the predominant language at the time, the Slovenian national spirit spread through music. A fine example are Mašek’s musical settings of works by Prešeren, Gazelles and Sonnets – a stylistic blend of classicism and early romanticism. However, these two works are technically very simple, most probably due to lack of proficient performers able to tackle more challenging music repertoire. The musicologist Dragotin Cvetko pointed out that the composer’s limited knowledge of Slovenian prevented him from fully immersing himself in Prešeren’s poems, which likewise influenced the musical expression of his compositions. Mašek’s son Kamilo had more success with setting Prešeren’s poems.

During this period, Mašek scored an extensive output, the first Slovenian cantata Kdo je mar? (Whoever?, a musical setting of the celebrated ode by J. V. Koseski) and a patriotic orchestral work Slovenska uvertura (Slovenian Overture). He was a prolific composer, though of somewhat less profound invention.

Maia Juvanc

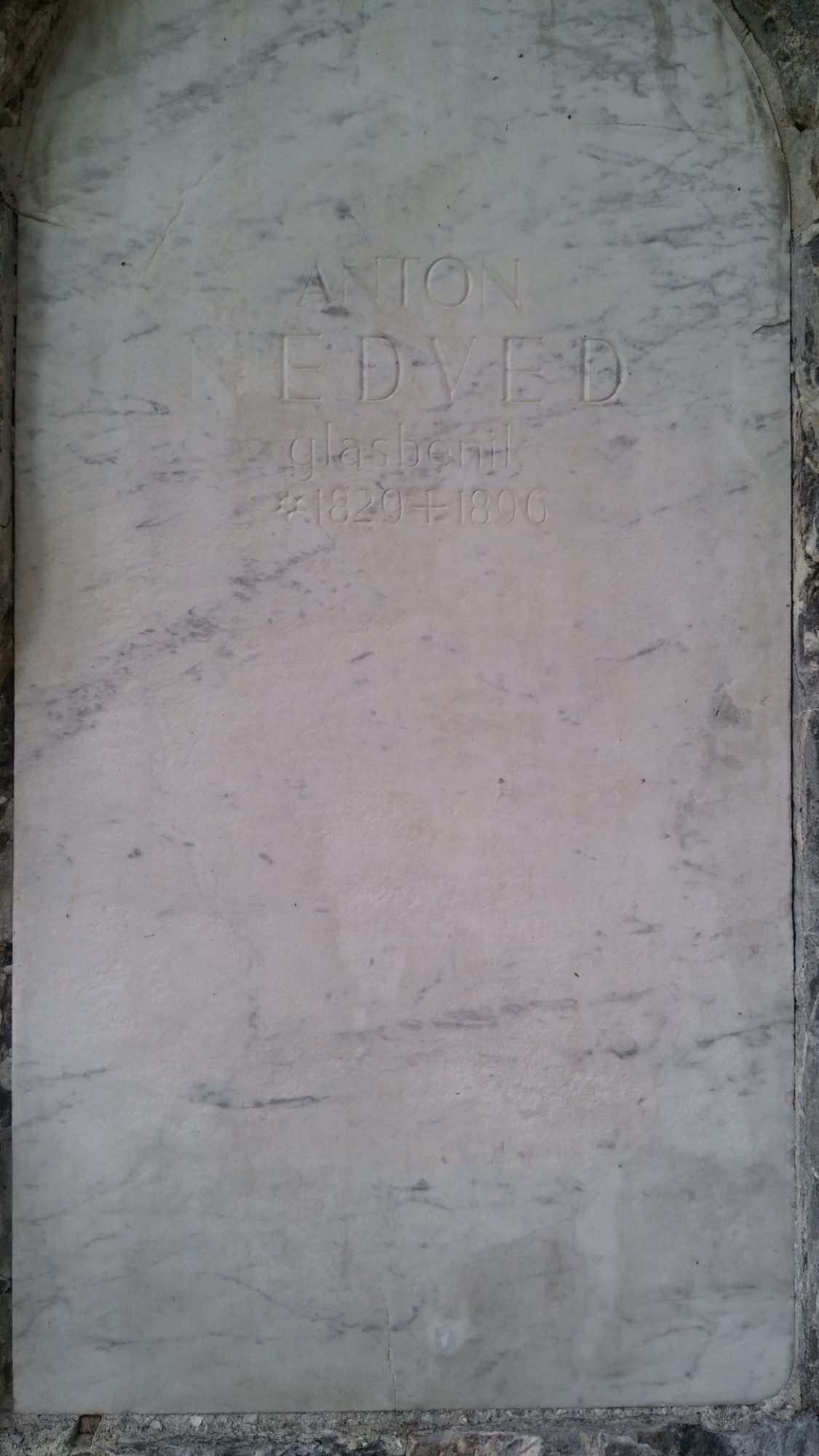

Anton Nedvĕd

Czech-born Anton Nedvĕd (1829–1896) made his mark in Slovenia as an accomplished choirmaster, singer, conductor and composer whose music was extremely popular among Slovenians for its pronounced patriotic sentiments. As an educated musician, Nedvĕd applied all his expertise to establishing Slovenian musical culture during the surge of national awakening.

Educated in Prague, he sang at a local theatre, and then worked at a Brno theatre, before finally moving to Ljubljana, where, in 1856, he was appointed manager and music director of the Philharmonic Society. Able to fully realise his aspirations in Ljubljana, he worked in various musical fields, including teaching at a public music school, theological seminary and teacher-training college.

As member of the circle of Bohemian intellectual expatriates who were at the time emigrating to Ljubljana, he ardently applied himself to ameliorating the deficiencies in Ljubljana’s musical life. Namely, at the time, the Philharmonic Society had neither a choir nor permanent orchestra membership. He formed a male choir, and encouraged female singing, thus advocating a practice that was taken up as their main activity by reading societies. He promoted the development of Slovenian culture and was instrumental in establishing the Glasbena matica Music Society and the Ljubljana Reading Room. He conducted the Ljubljana Reading Room Choir to great success over its first year, primarily programming works by Slovenian composers. However, he also faced opposition in devising the Philharmonic Society’s concert life. This was because his programmes included more challenging works by European composers and pieces by Slavic and Slovenian composers, which confounded the limited expectations of provincial audiences. He thus enhanced the concert repertoire and set an inspiring example to his successors.

His composing style displays a distinctive national quality, which rendered it highly appealing to Slovenian performers. He focused most of his creative energies on composing for male and mixed choirs. One of his most notable compositions, Nazaj v planinski raj (Back to the Mountain Paradise), is a musical setting of a poem by Simon Gregorčič.

He scored most of his lieder for female voice and piano, and predominantly set Slovenian poems. In composing religious works, he relied more on the liedertafel tradition than on Caecilian guidelines. An example from this output is the mass Slava stvarniku (Glory Be to Our Maker), which is considered one of the first Slovenian compositions of this kind written for male choir.

He had a crucial influence on Slovenian music education, and published the first Slovenian textbook, Kratek nauk o glasbi (Short Overview of Music Theory, 1863), and other manuals aimed at spreading the theory of Rudolf Weinwurm, a prominent Viennese singing teacher. He devoted most of his attention to enhancing vocal culture, an art that, due to scarce educational opportunities, was still at an amateur level in Slovenia at the time.

Maia Juvanc

Vojteh Valenta

Vojteh Valenta (1842–1891) was an amateur musician, baritone, composer and concert promoter. A proponent of the Slovenian national movement, Valenta conducted the Ljubljana Reading Room Choir and established the Glasbena matica Music Society Ljubljana.

He initially obtained his basic musical education at a public music school in Ljubljana, where he attended the same class as Fran Gerbič for two years. He was a member of the Philharmonic Society from 1861, singing in its choir and purportedly receiving tuition from Anton Nedvěd at the Philharmonic singing school. He also sang in the National Reading Room Choir, which he occasionally conducted; he also devised programmes for its concerts, including excerpts from famous operas by Smetana, Gounod and Meyerbeer in the early 1880s. As a soloist he sang the role of Poljanec in the premier production of the operetta Tičnik (The Aviary) by Benjamin Ipavec. In 1867, he sat on the board for the establishment of the Dramatic Society and became one of its first members. Within the context of the Society, he taught at its singing school, performed as an actor and singer, and occasionally composed music for theatre productions and conducted performances.

His greatest contribution to enriching Slovenian culture was the establishment of the Glasbena matica Music Society. He dedicated his life to organising Matica’s activities, serving on its board and later becoming an honorary member.

While occasionally composing vocal music, his output never merited inclusion among important composing legacies. His music followed the style of early romanticism. He scored some four-part male choral pieces, including Naš maček, Miserere za pokop pusta, Sirotka, Pod lipo, Pri oknu sva molče slonela, Poljub, Zakaj me ljubiš (Our Cat, Miserere for Ash Wednesday, Little Orphan, Under a Lime Tree, We Leaned Silently by a Window, A Kiss, Why Do You Love Me?).

Maia Juvanc

Jurij Flajšman

You can read the biography HERE.

Gregor Rihar

You can read the biography HERE.