The Marij Kogoj memorial room, i.e. a permanent collection dedicated to the composer, is housed in an eleventh-century Gothic building, which also houses the town library, in Kontrada Square in the old town centre of Kanal, a settlement lying on the left bank of the Soča River frequently referred to as Kanal ob Soči.

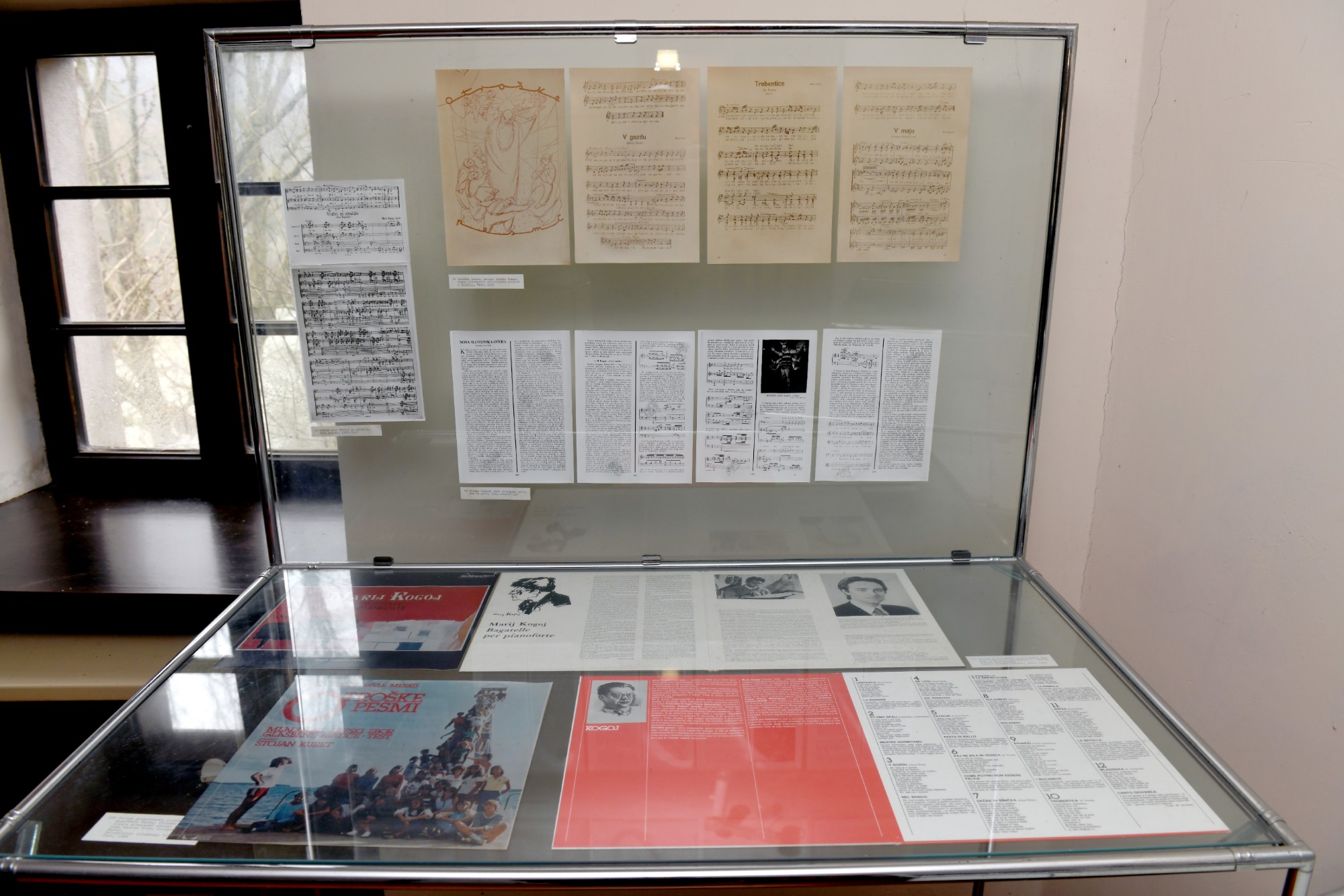

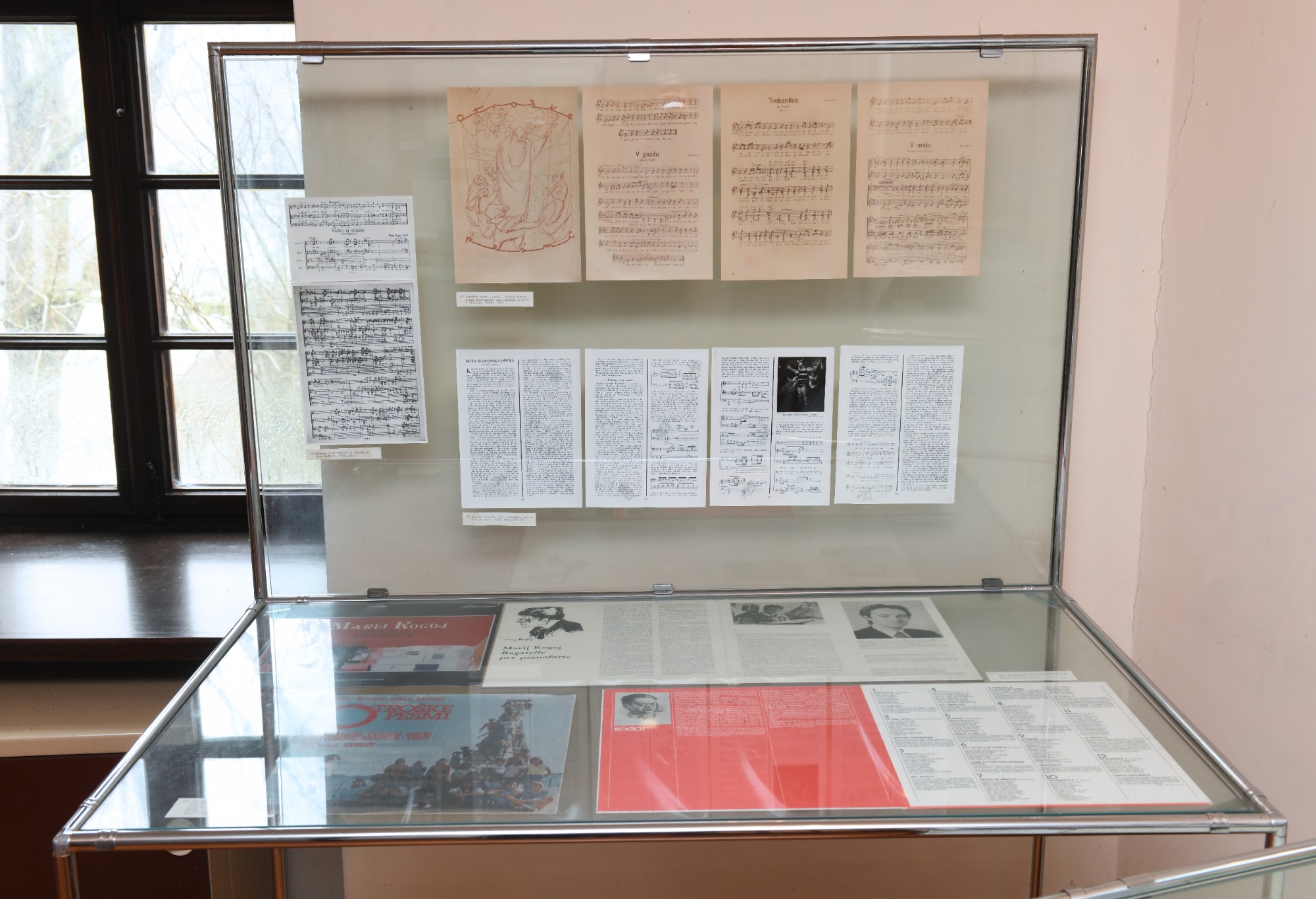

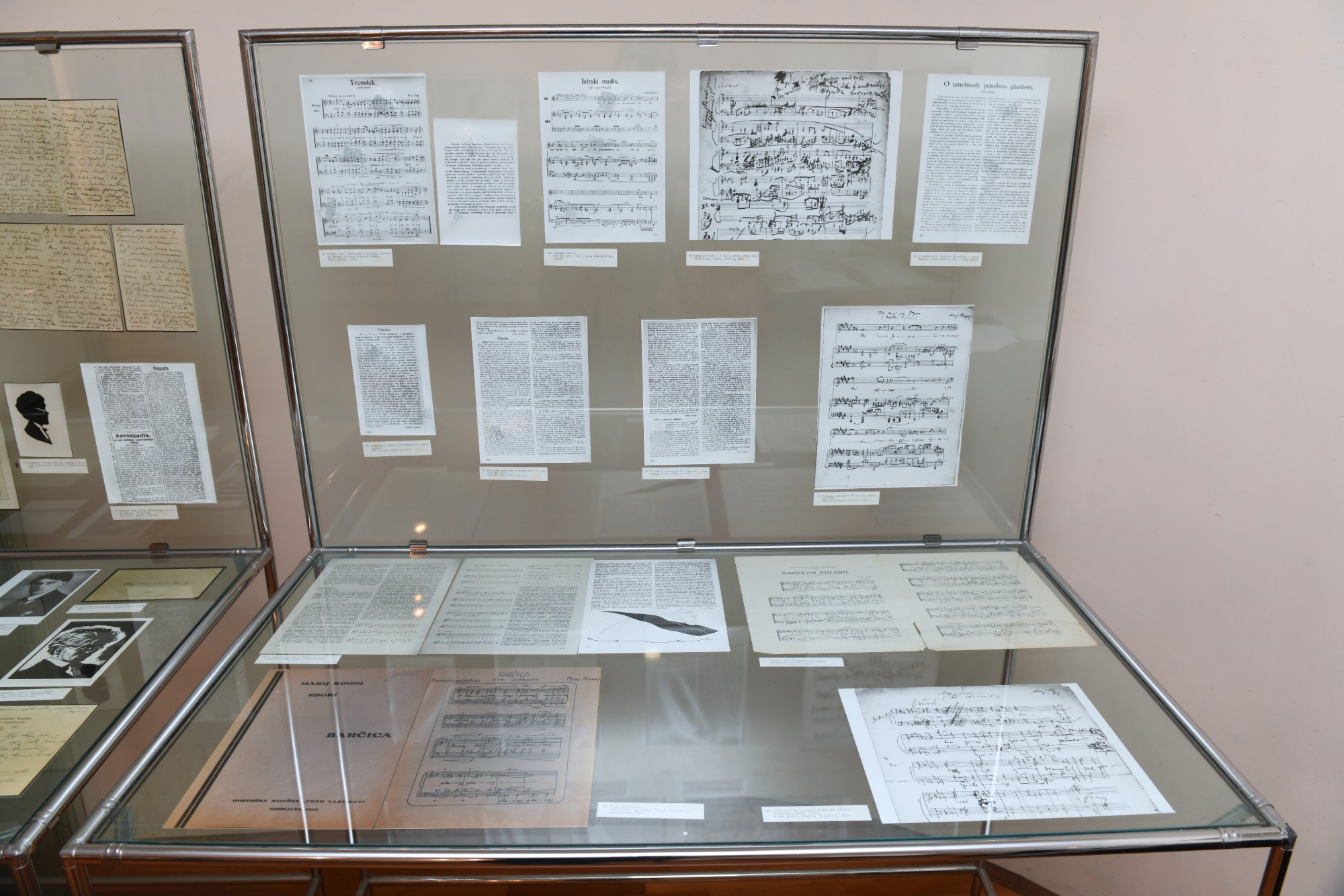

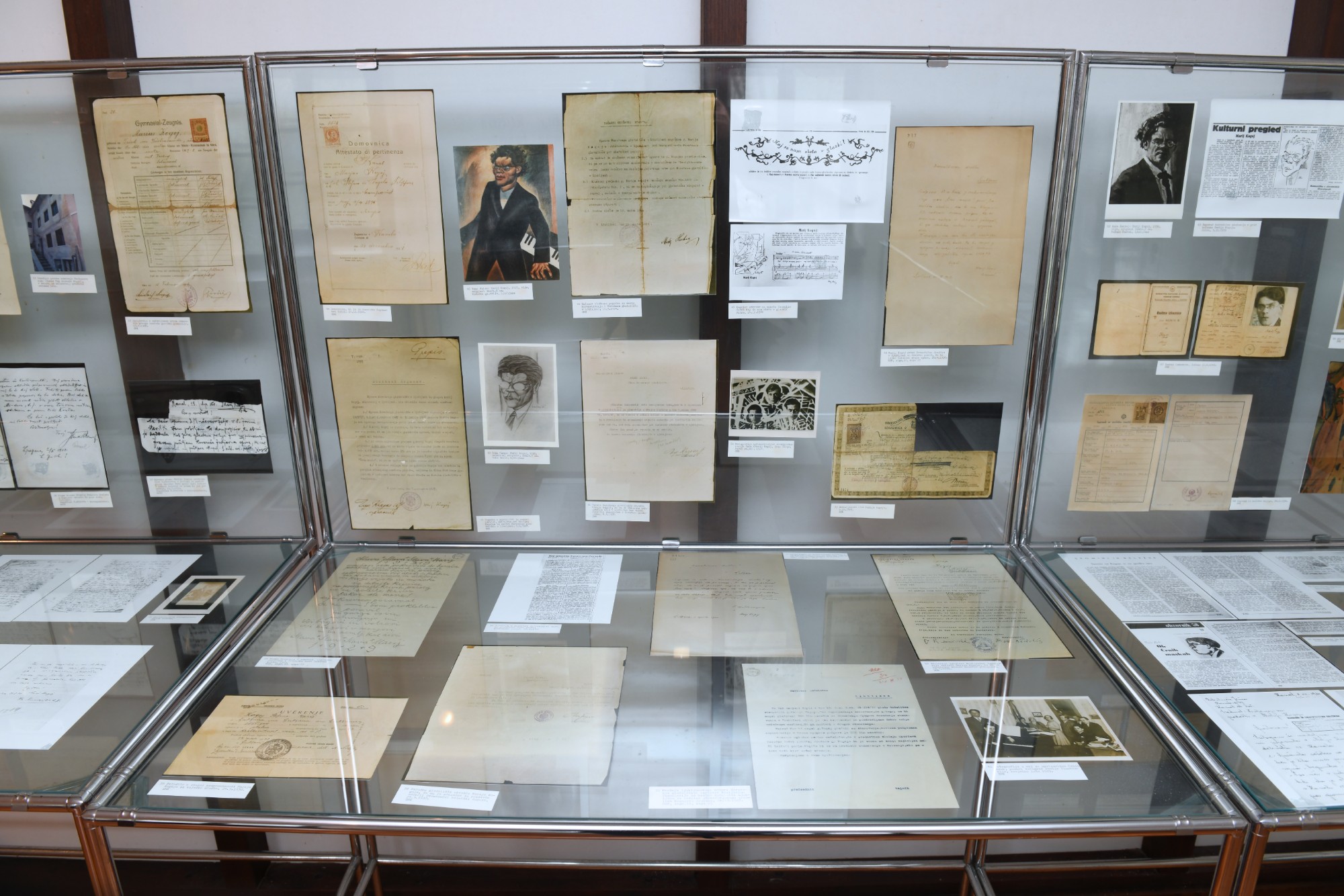

The exhibition charting the life and work of the Slovenian expressionistic composer Marij Kogoj was opened in 1989 as a division of the Regional Museum Nova Gorica. Encompassing 107 exhibits and curated by Pavle Merkù, a composer from Trieste, and historian Metka Nusdorfer Vuksanović, the show is divided into two parts, focusing either on Kogoj’s biographical details or his creative work.

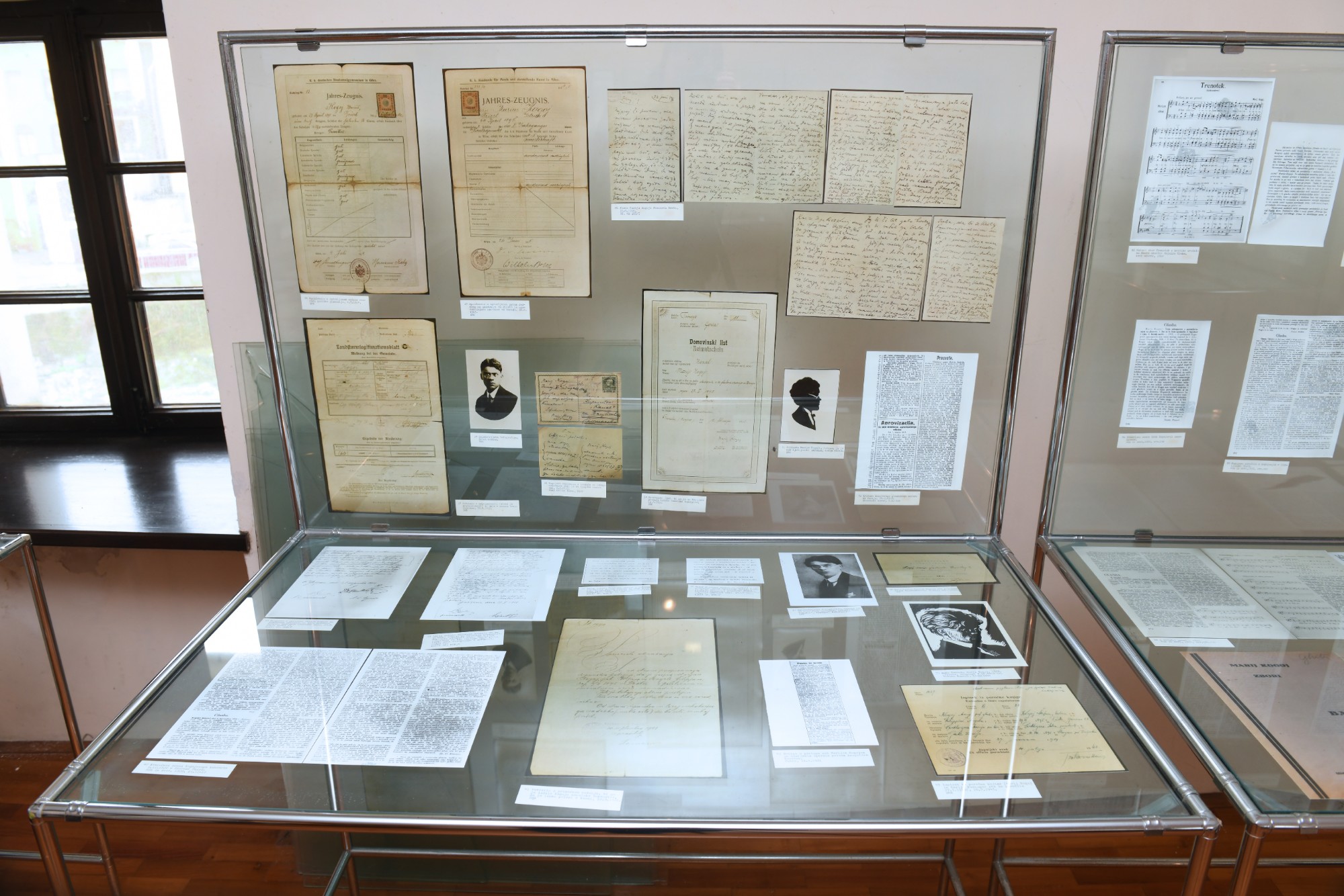

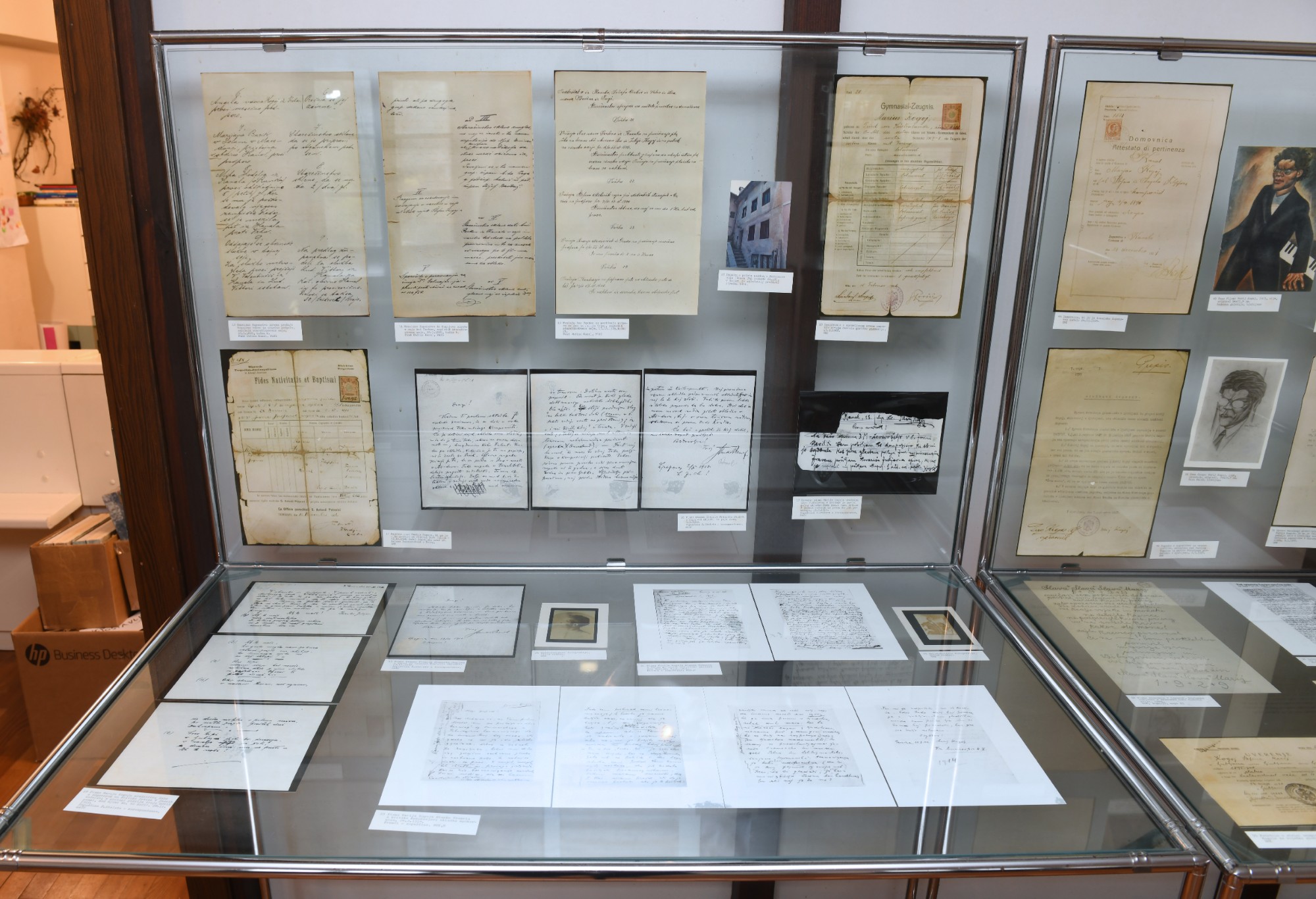

The biographical section chronicles the composer’s life by segmenting it into subdivisions, beginning with the Trieste period, which includes his birth and early childhood, the Kanal period, the time from 1899 when he was growing up as an orphan, and the Gorica period, which charts his grammar school years and early beginnings in music. The Vienna period was when Kogoj pursued further studies in music. Ultimately, the Ljubljana period, after 1918, witnessed the composer experience severe financial hardship and mental distress resulting from his disillusionment with the sobering reality of a world indifferent to his spiritual and intellectual aspirations.

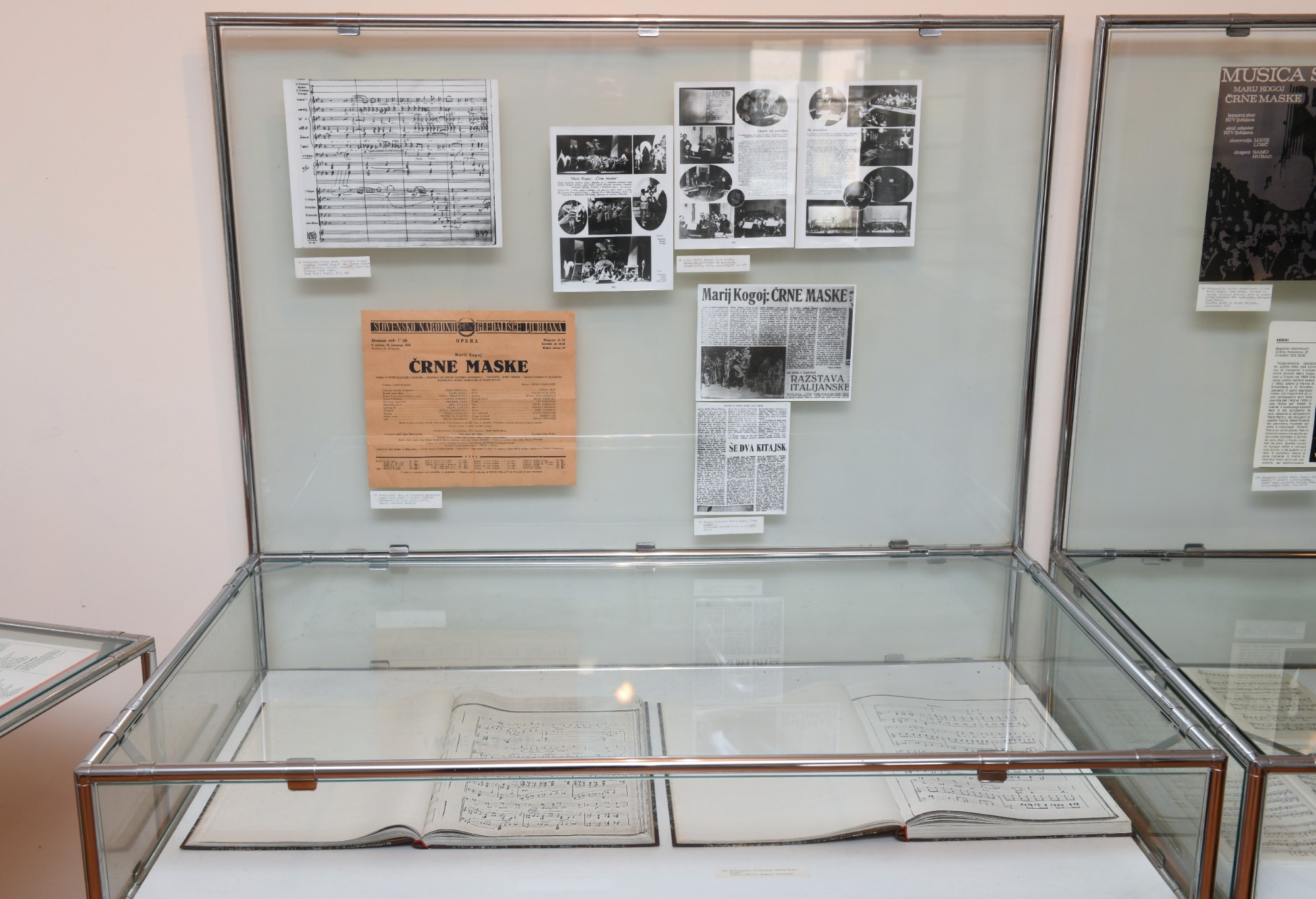

The collection dedicated to Kogoj’s musical work illustrates the progression of his output, from the first choral pieces to his only opera, Črne maske (The Black Masks), the supreme achievement of his musical endeavours and evidence of the contact of Slovenian art with European musical trends of his day.

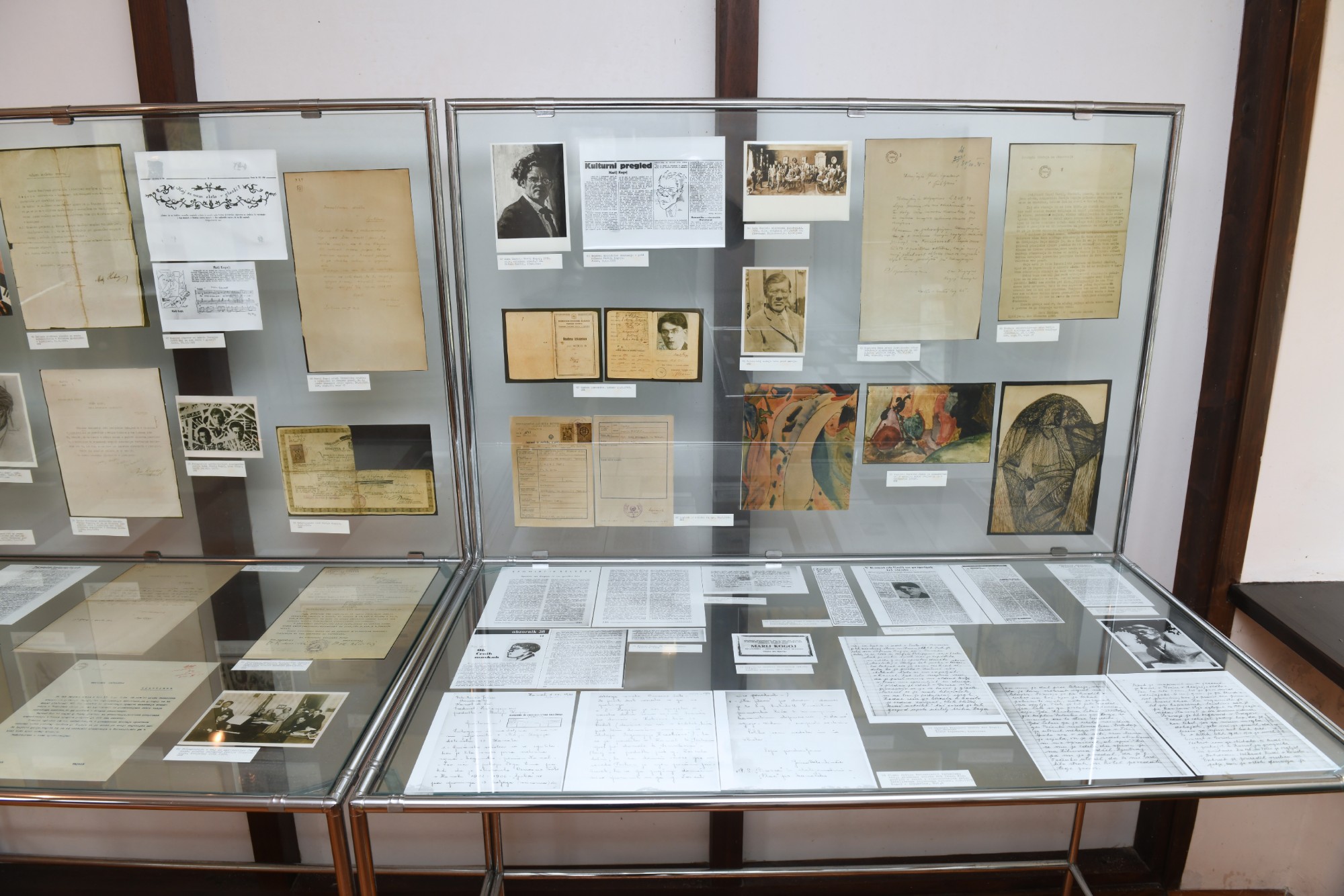

Among the highlights of the exhibition are Kogoj’s letter from 1929, containing unmistakable traces of his deteriorating mental health, some of his paintings, as well as presentations of Črne maske and media coverage of this outstanding and unique example of expressionistic opera in Slovenia. On view are the opera’s original score and an article about the piece written in 1929 by Stanko Vurnik for the Dom in svet (Home and World Affairs) newspaper, as well as an article about the work that appeared in the Ilustracija (Illustration) magazine.

Some of the exhibits shed light on Kogoj as a music critic and essayist.

Website of the Marij Kogoj Memorial Room

E-mail: tic.kanal@siol.net

Marij Kogoj

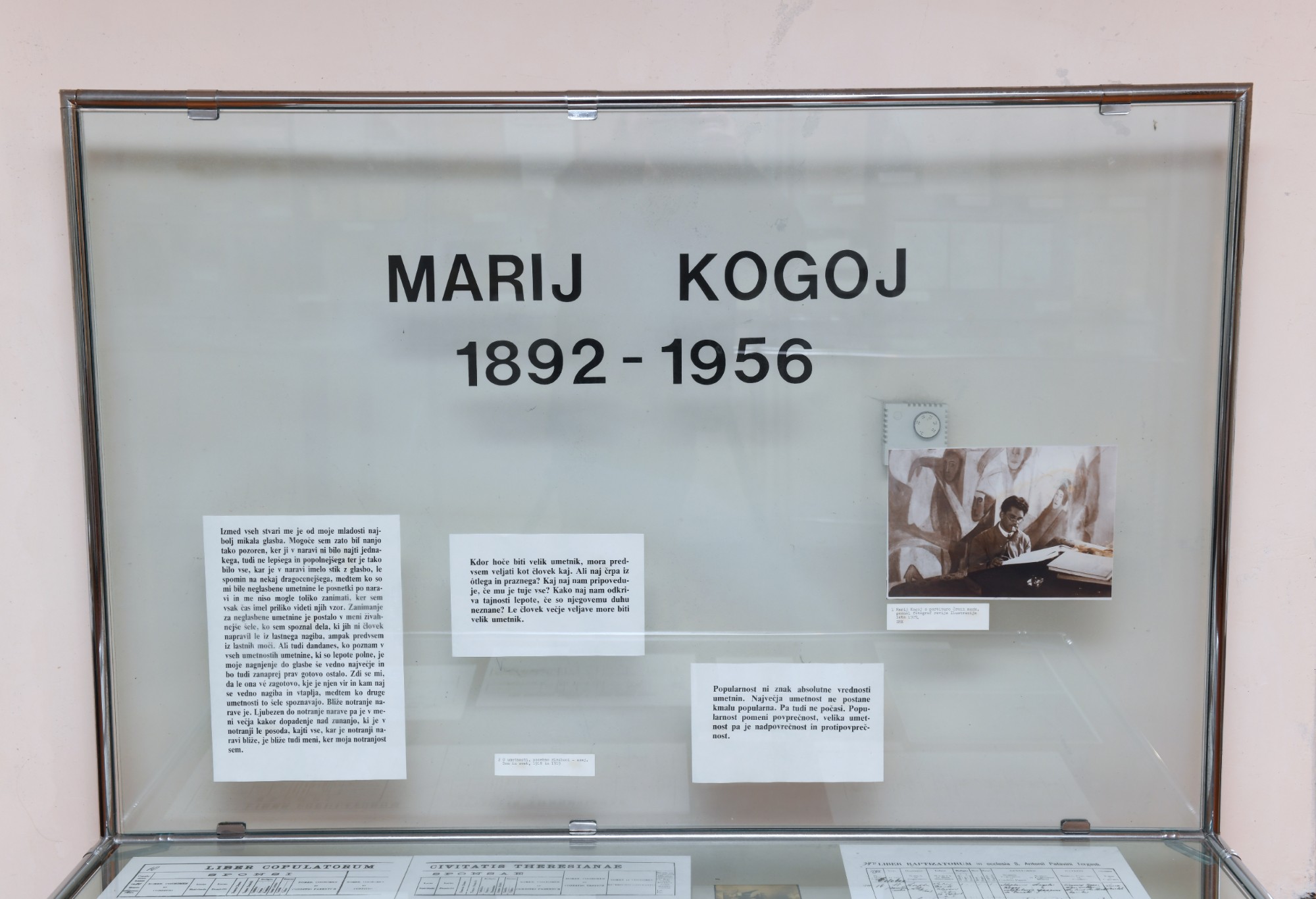

Composer Marij Kogoj (1892–1956) is a notable representative of early twentieth-century European music, when new compositional techniques were adopted and new approaches created that either redefined tonality or abandoned it. Emerging at the turn of the 20th century, expressionism deepened the nineteenth-century aesthetic that sought to depict an expressly subjective perspective, taking it to new heights and resulting in highly intimate articulations of inner human recesses. The new compositions resembled psychological maps or psychograms, and renounced the aesthetic conventions of the ‘beautiful’ in accordance with the spirit of the time, which encouraged the development of Freud’s psychoanalysis. Surrounded by these impulses, it was in Vienna in 1914 that Kogoj began to study composition with Franz Schreker, and instrumentation under the celebrated Arnold Schoenberg. That same year, Kogoj scored his remarkable choral work, Trenotek (Moment), which generated widespread interest and, published in Novi akordi (New Chords), heralded the emergence of musical expressionism in the broader Yugoslav context. Viewed from the perspective of Slovenian musical culture, Marij Kogoj’s art should be considered as a ‘leap’ from traditional attempts at a national opera – examples of the genre continued until as late as 1923 – to an expressionistic opera, rather than a shift from operetta in “the old numerical style” to expressionistic musical drama, and as step beyond nationalism into supranational symbolism.

Regarded as Kogoj’s crowning achievement, the opera Črne maske (Black Masks, 1927) takes as its text the eponymous play by Leonid Andreyev, and through its literary symbols addresses issues of the human soul and identity. This solitary example of expressionistic opera in Slovenia utilises the symbolism of inner conflict, the human struggle with one’s hidden darkness. On a par with great operatic masterpieces, works as monumental as Salome and Elektra by Richard Strauss, according to music scholars, Kogoj’s opera is a vital work that placed Slovenian music creativity in the context of contemporary European trends.

It was a change of identity, i.e. a personality crisis in his early youth, that influenced Marij’s exploration of intimate human psychology. Born in 1898 as Julij, the composer’s split identity resulted from the tragic death of his younger brother, whose name he had no choice but to adopt, being called by his brother’s name by adults. When he was six years old, his father died, and a year later the children were left without their mother, who it is presumed went to Egypt to work as a wet nurse, becoming a so-called Alexandrian woman.

Although Kogoj’s contemporaries recognised the value of his advanced music idiom, they did not share his artistic ideas. Furthermore, the conservative public received his works with equal reserve. For want of like-minded fellow musicians, Kogoj joined the community of young writers and artists, members of the Slovenian avant-garde. This sense of isolation and of being different that filled the composer is captured in the group painting entitled Slovenian Composers by Saša Šantel, displayed in the Slavko Osterc Hall of the Slovenian Philharmonic. Kogoj’s conviction that, “all art should be futuristic – that is, express a vision of the future – otherwise, it is of no use”, garnered only a few adherents in Slovenia, although it generated much attention.

Having been diagnosed with schizophrenia, Kogoj’s mental illness greatly affected his work after 1932. Hindered in his musicals efforts, Kogoj’s disability possibly contributed to the fact that in the post-war period more progressive musical impulses in Slovenia took longer to germinate.

Maia Juvanc