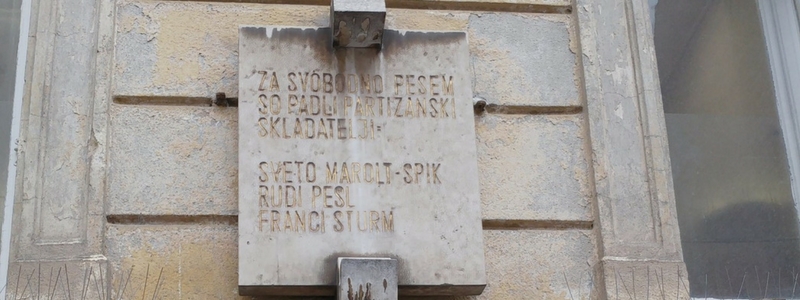

The plaque commemorating fallen composers was attached to the façade of the Academy of Music in Ljubljana. The memorial is dedicated to resistance fighters who died during WWII while engaged in the struggle for national liberation as members of the 14th Division and during the German offensive on Paški Kozjak. These fighters included the Partisan songwriters Rudi Pešl (1916–1945), and Sveto Marolt-Špik (1919–1944), who composed the anthem of the 14th Division, Zaplovi pesem (Sail Away, Song), based on a poem by Kajuh. The memorial also commemorates Franc Šturm (1912–1943), composer of the unofficial Partisan resistance anthem, Hej brigade (Hey Brigades), who had followed contemporary neo-classical, neo-baroque and expressionistic music trends before the war.

The engraved inscription reads: “Partisan composers Sveto Marolt-Špik, Rudi Pešl, Franc Šturm gave their lives for the freedom of song.”

Sveto Marolt-Špik

Composer Svetozar Marolt (1919–1944), whose Partisan nickname was Špik, was born in Zagorje ob Savi. Before World War II, he attended the Music School of Glasbena matica Music Society Ljubljana and the Ljubljana Music Conservatory, where he studied composition and piano with Anton Ravnik and Anton Trost.

He predominantly composed religious lieder (O bodi čaščena, Marija, mati božja – Hallowed Mary, Mother of God), and compositions addressing the theme of love (Zvezde žarijo, Pesem ljubezni – Glowing Stars, A Song of Love). After 1941, when joining the partisan resistance forces like many other Slovenian composers and culture professionals, his creative output acquired a revolutionary overtone. He took an active part in the cultural group of the 14th Division, whose anthem Zaplovi pesem borb in zmag (Soar, Song of Combat and Victory) he composed in 1943.

During the National Liberation Struggle Marolt-Špik joined the ranks of the approximately 71 composers who wrote altogether 500 pieces, predominantly choral works displaying stylistic parallels with the sixteenth-century music characteristic of Protestantism and with music of the national awakening movement and late nineteenth-century Reading Room societies, and which broke ties with pre-war modernist tendencies in Slovenia. The more common wartime repertoire of massive unison choir songs was complemented by a more intimate, chamber output of over 50 lieder, which includes Marolt’s compositions. His lieder, musical settings of poems by Karel Destovnik-Kajuh (Bosa pojdiva, Sanjala si – Let Us Go Barefoot; You Were Dreaming) and Matej Bor (Pesem talcev – Song of Hostages), have artistic merit, despite the simpler musical language intended to foreground the central ideas of the wartime period. Marolt-Špik thus ranks among composers such as Janez Kuhar, Marjan Kozina, Karol Pahor, Makso Pirnik, Rado Simoniti.

Marolt’s musical talent and inspiration enjoyed recognition even posthumously, and in 1947 his compositions were featured in the collection Štiri pesmi za glas in klavir (Four Songs for Voice and Piano). Marolt was shot in the Savinja Valley.

Maia Juvanc

Rudi Pešl

Franc Šturm

A composer aspiring to blend the musical heritages of Ljubljana, Paris, Prague and other cultural hubs of Europe, Franc Šturm (1912–1943), on the eve of a world war, trod an artistic path from his native land to the Czech and French capitals and back to his homeland, where he lost his life as member of the partisan resistance forces. Written initially in the neo-baroque style and then gradually acquiring elements of modernism, Šturm’s compositions bear eloquent testimony to his personal history.

Having developed an interest in music early on, Šturm took up musical studies in the class of Slavko Osterc while attending grammar school. Completing his studies with Osterc, Šturm entered the Prague music conservatory, studying under Josef Suk and Alois Hába. It was Hába who introduced him to the quarter- and sixth-tone system of composing and guided him in his first endeavours at musical creation. In contrast, Suk had little influence on Šturm.

In 1935, his return to Ljubljana did not live up to expectations; hoping to find a friendly circle of composers, he was unable to build a rapport with unapproachable fellow musicians. Even Demetrij Žebre and Marijan Lipovšek, Šturm’s schoolfellows at Prague, did not share his views. Šturm thus recorded his laments: “Osterc keeps playing at being a dictator… I see that no cooperation whatsoever is possible. Externally, we are still a united front, but internally we are divided, at odds even with Žebre and Lipovšek.” His loneliness resulted from different aesthetic opinions and lack of social connection among the interwar Slovenian composers. There was a gaping chasm between the nineteenth-century orientation of Lucijan Marija Škerjanc and Blaž Arnič and the progressive leanings of Osterc, Žebre, Danilo Švara and others, whereas the formerly controversial composer Marij Kogoj had become mentally ill early on.

Šturm was rather unfortunate in finding employment. His jobs included teaching at a private music school, giving tutorials in quarter-tone scale, and teaching at Jesenice, but these attempts proved largely futile. In 1938, Šturm entered military service in Maribor, and then went to Paris to take up further studies. Returning to Slovenia in 1940, he joined the partisan resistance movement. He was killed in action on 11 November 1943 in Iški vintgar.

Scored as a twenty-year-old student of Slavko Osterc, it is already Šturm’s early compositions, pieces echoing European and Slovenian modernist tendencies, that reveal themselves as meaningful approaches to forms of the previous centuries. In keeping with Osterc’s predilection for fugue and canon, Suita (Suite, piano, 1932) is composed of baroque genres. Sonata za klavir (Piano Sonata, 1932) is an amalgam of organically interlaced movements that flow into one another seamlessly, without pause.

Šturm honed his Godalni kvartet (String Quartet), a meaningful work scored in his second creative period (1934–43), in Paris. A prominent role is assigned to polyphony, whose density is intensified to an agreeable proportion by developing musical finesses. He furthermore adopted an athematic style – choosing not to connect the fragments that serve as the building blocks of the composition with an underlying theme. Not limiting his output to string ensembles and piano, Šturm’s other works include Fantazija za orgle (Organ Fantasia), Sonata za violino solo (Sonata for Solo Violin) and Fantasie nocturne for alto saxophone and piano. Moreover, he wrote compositions in quarter-tone scale, for example the missing Godalni kvartet (String Quartet, 1935) and Mala muzika za dve violini (A Little Music for Two Violins, 1938). Arriving in Paris in 1939, Šturm had hoped that the local composers would take him under their wing, but the strained atmosphere on the brink of war frustrated his expectations.

Šturm seemed to have abandoned modernism while a member of the partisan forces. Nonetheless, it would have been improper to consider him the sole author of the resistance choral works Hej, brigade (Hey Brigades) and Petindvajset (Twenty-five) as well as the lieder Partizanska romanca (Partisan Romance) and Materi padlega partizana (To the Mother of a Fallen Partisan), as many partisan compositions were not written down until after the war, from memory. A notable pre-war vocal work is De profundis (1935), a setting of a poem by Alojz Gradnik for voice and woodwind, brass and string instruments. With rare tutti passages, the ensemble’s transparent sonority tends to give precedence to the singer. The basic moods, despair and hope, are outlined as early as in the first movement.

Lev Fišer